I’m pleased to report that my first history book, Lincoln’s Lost Colony: The Black Emigration Scheme of Bernard Kock, has been released by McFarland. The book took me 11 years to research and write. It wouldn’t have taken so long had I not elected to thoroughly footnote and index it. I elected to do this because the subject matter is controversial. I wanted the book to stand up to academic scrutiny. I hope it finds its way into libraries throughout the country.

My work on the book started as a blog post more than a decade ago. I’ve been collecting family history for a blog, Thompson Family History, since my father passed. That process started, of course, with putting together a family tree, which no one on my branch of the family had bothered to do. I have to admit that as a young man full of piss and vinegar I didn’t give a hoot about the relatives who had come before me. Late one night, after I had started to care, I discovered that my third great grandfather was someone named Bernard Kock. I had no idea who he was. He came from Germany, traded in tobacco, and eventually became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

A quick search of the Internet revealed why, perhaps, no one had ever talked about him and why some Kocks who came after him wound up in convents. I found his exploits chronicled in a blog about grisly American history stories that your teacher never told you. To this day, he is still evicerated by historians writing about the “Cow Island” affair. He has alternatively been called a “swindler,” a “scoundrel,” and “a devil.”

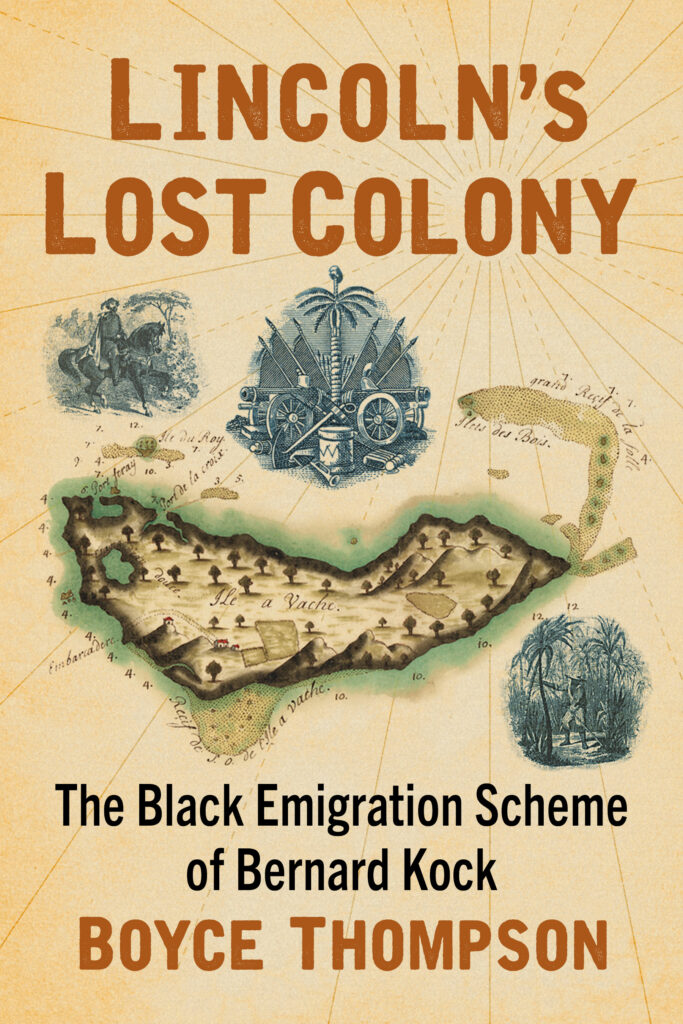

Bernard Kock, at one time a very wealthy trader and president of a New Orleans railroad, visited the White House and got President Lincoln to sign off on a deal paying him $50 “a head” for every formerly enslaved person he took to an island off the coast of Haiti where he planned to establish a cotton plantation. The Union was starved for cotton at the time, and Lincoln was looking for ways to establish the efficacy of Black emigration. Througout his political career, Lincoln preached the gospel of Black colonization.

Most historians who have written about this subject heap all, or nearly all, the blame for its failure on Kock, who has become a kind of scapegoat through the years. They conveniently overlook the culpability of the Lincoln administration, which turned a blind eye to decades of failure of Haitian emigration; Kocks investors who reneged on their part of the deal; the brutal treatment of the colonists by Haitian guards; and the subterfuge of American consuls in Haiti. Kock, of course, deserves a big portion of the blame since he instigated and executed the venture. But the book exposes the culpability of his partners as well.

I couldn’t begin to estimate how many days, weeks, and months when into the research and writing of this book. In the beginning, before I had gathered all the facts and opposing points of view, it was difficult to figure out what really happened. Eventually, though, I figured out who was lying or bending the truth to their benefit. In the 1860s, it would have been much more difficult to “fact check” official correspondence. Some participants in the Cow Island scheme lied with impunity.

I kept thinking as I wrote the book of the parallels to U.S. politics today. In the 1860s, no line had been drawn separating poltics and business. Politicians took positions in business ventures that required government investment. Business people gave liberally to politicians and expected something, maybe even a lot, in return. And then, as well as today, politicians naively pursued “big ideas” that would earn them notarity, sometimes ignoring the lessons of the past. Oh, and a lot of people lied for their convenience.