I detoured from a business trip this fall to travel through parts of Tornado Alley, which extends from North Texas through South Dakota. Big twisters seem to touch down there with alarming frequency, causing major building damage and heart-wrenching loss of life. I wanted to see how homeowners and builders there have responded; how they are protecting homes from the next big one. My journey started in Joplin, Mo., then I dipped down into Moore, OK., and finished in the Dallas suburbs of Garland and Rowlett.

Before leaving, I read as much as I could about designing homes to resist high winds from tornadoes and hurricanes. It’s clear that there isn’t much you can do to defend against an EF5 Tornado, like the multiple-vortex storm that touched down in Joplin, Mo., in 2011 and the two-mile-wide twister that hit Moore in 2013. With winds of more than 200 mph, they destroyed everything in their path, including hospitals and schools built with steel and concrete. New homes were no match for the EF4 tornado that visited the Northern suburbs of Dallas during the 2015 holiday season.

But engineers who investigate find that most tornado – and hurricane — damage is done by lesser winds around the periphery of a big storm, or by less violent storms. Much of that damage can be prevented by building to the wind-safety standards of the latest model codes. The International Code Council, for instance, publishes a model construction standard for protecting homes from winds that reach 135 miles an hour, the strength of an EF2 tornado or a Category 3 hurricane. For any tornado stronger than that, you are better off seeking refuge in a tornado shelter anyway, whether inside the house, in the yard, or in a nearby community center.

Tornado categories:

EF2: Up to 135

EF3: Up to 165

EF4: Up to 200

EF5: Greater than 200

Hurricane categories:

Cat. 3 up to 129 mph

Cat. 4 up to 156

Cat. 5 157 or greater

Joplin, Missouri, residents didn’t have much time to prepare before a massive twister set down one afternoon in May. Civil defense sirens sounded 20 minutes before the tornado struck. The sirens here are common enough that many residents didn’t heed them. The twister started small but quickly grew in intensity as it traveled through rural areas. It struck Joplin with catastrophic results, killing 158 people, flattening commercial buildings, and destroying whole neighborhoods.

Most homes in the most devastated neighborhoods have been rebuilt, though you still see the occasional empty lot. In some places, there may be a new home on the lot but the sidewalk and street around the house are still beaten up. The city council, in the wake of the tornado, floated a proposal to require storm shelters in every new home. Four years later, it settled for provisions that require hurricane clips to fasten roofs to walls, beefed up concrete foundations, and foundation anchor bolts spaced a maximum of 4 inches on center. Otherwise, the building code relies on a version of the ICC that only provides protection from 90 mph winds.

By contrast, the tornado code in Moore, Oklahoma is designed to protect homes from an EF2 tornado with winds up to 135 miles per hour. The city took this action after a third major tornado in 15 years destroyed big swaths of the city. As a result of the code, new homes in Moore look a little different than homes in other places. They are built primarily with brick or stone. Few dormers top their hipped roofs. You don’t see many big eaves and overhangs that high winds could lift.

As in Joplin, builders are required to tie rafters to the walls with hurricane clips and anchor foundations to wood base plates in the walls. Moore also took the extra step of requiring walls to have lateral support. Most homes are built to resist vertical forces like the weight of snow setting on the roof, appliances and furniture in the house, and the building itself. But high winds also exert lateral forces parallel to the ground that can come from any direction. To resist lateral loads requires the use of OSB or plywood sheathing in the walls, additional base anchor bolts, and nails spaced closer together.

One of the biggest changes in Moore was to require garage doors fortified to withstand 135-mile-per hour winds, like you see in hurricane-prone regions of Florida. In the wake of the tornado, inspectors found that high winds easily infiltrated houses through weak garage doors. Once inside, the winds ripped off the roof and exploded out walls, much like what happens when you pop the top off a shaken soda can.

Most of Moore’s major builders don’t object to the requirements, based on newspaper reports. Chris Ramseyer, an associate professor of engineering at the University of Oklahoma in nearby Norman who helped design the Moore code, estimates that the provisions add $1.50 to $2.20 per foot to the cost of a home. That works out to about $3,000 or $4,000 for a 2,000-square-foot home, less than the cost of a granite countertop. Even so, few jurisdictions within Tornado Alley have followed Moore’s lead.

It’s hard to find evidence of damage from the series of 12 or more tornadoes that ripped through the Dallas suburbs in 2015. Homes in the otherwise peaceful suburbs were quickly repaired or rebuilt. American Plywood Association (APA) engineers, who investigated afterwards, found that the damage here was surprisingly high to homes hit by lesser winds. Smaller tornadoes “produce winds which a carefully constructed building can be expected to withstand,” they reported.

Most of the damage was due to poor connections between roof and walls. Framers used toenails to connect roof framing the exterior walls. Inexpensive light-gauge metal connectors could have saved many of the roofs. “With these, the load is resisted in directions perpendicular to the nail shank rather than acting to pull the nail straight out,” the APA reported. “Use of these metal connectors was only observed in one case among the homes where loss of the roof structure occurred.”

Another common, very preventable cause of failure: attaching walls to foundations with pins instead of anchor bolts. In most cases, framers shot pins from nail guns to attach the bottom of support walls to concrete-slab foundations. The technique saves time and money, and it also meets many local building codes. But most “modern” building codes, the report says, call for “deformed steel anchor bolts to be embedded into reinforced concrete foundations for attachment of wood framing.”

Other buildings crumbled for lack of lateral bracing in walls. They were often sheathed with 1/8-inch laminated fiber, rather than thicker OSB or plywood. The thin material failed to transfer loads within walls, especially at corners and between floors. Many exterior walls were clad with poorly installed brittle brick veneer, which got hammered by the high winds. “Falling brick from veneered walls, columns, and chimneys were observed across a wide range of wind speeds in the impacted areas, representing a considerable threat to life safety.

The APA report revealed large breaches in homes due to the failure of windows and garage doors. Even in areas with low to moderate wind speeds, weak apertures gave way, allowing air to get inside and pressurize the building. The pressure blew out roofs and walls, allowing rains to soak interiors. Insurance companies report that in this situation mold can begin forming within 24 hours.

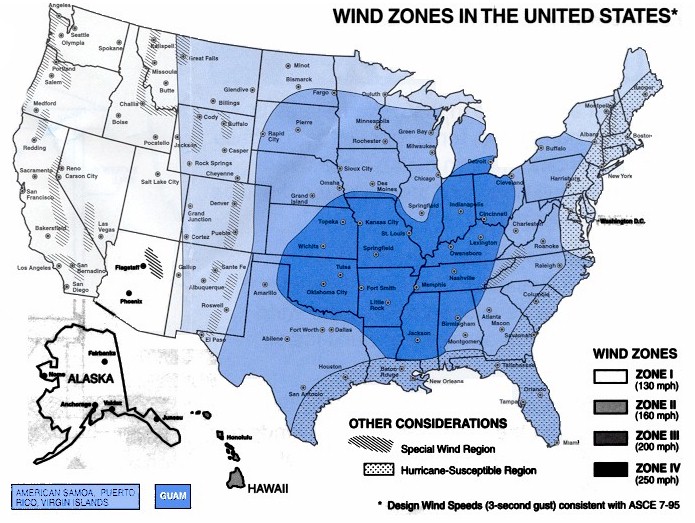

(Use FEMA Tornado Map)

FEMA maps show that a surprisingly large percentage of the country is subject to high winds from tornados and hurricanes. If you are building in these regions – whether in Tennessee, South Carolina, or South Dakota – it’s worth having a discussion with your builder about damage-prevention strategies. Some builders automatically include lateral bracing, hurricane clips, and anchor bolts in homes they build. Others will if you ask For reference, here’s what Moore’s tornado code requires:·

- Roof sheathing (OSB or plywood) nailed with 8d ring shank nails 4 inches on center along the edges and 6 inches on center in the field

- Roof framing no more than 16 inches apart on center. The minimal nominal sheathing panel size is 7/16

- Roof framing connections design for both compression and tension. They may include nail plates or steel connection plates.

- Roof framing connectors on rafters, web members, purlins, kickers, bracing connections. (check to see if they must be connected to) and the connections to interior brace wall top plans or ceiling joists.

- Gable end walls tied to the structure. They may include steel connection plates or straps. Connections should be made at the top and bottom of the gable end wall.

- Structural sheathing panels (OSB or plywood) are required for gable end walls.

- Hurricane clip or framing anchors are required on all rafter to wall connections.

- Upper and lower story wall sheathing nailed to the common rim board.

- Walls continuously sheathed with structural sheathing (OSB or plywood) using the CS-WSP method.

- Garage doors framed using the sheathed portal frame method CS-PF.

- No form of intermittent bracing shall be allowed on an outer wall. Intermittent bracing may only be used for interior braced wall lines.

- Nailing of wall sheathing (OSB or plywood) shall be increased to 8d ring shank or 10d nails on 4 inches on center along the edges and 6 inches on center in the field

- Structural wood sheathing shall be extended to lap the sill plate and nailed to the sill plate using a 4 inch on center along the edges. Structural wood sheathing shall be nailed to the rim board if present with 8d ring shank or 10d nails on 4 inches on center along both the top and bottom edges of the rim board.

- Garage doors rated to 135 mph winds or above

- Exterior wall studs spaced 16 inches on center